Post inspired and related to the ongoing Corona virus pandemic. But will not be looking at it from the angle of spreading, precautions, treatment etc. Leaving that to the experts and doctors. OK, will touch upon that, but only in order to set the perspective – as little as possible. Here I’ll discuss the ethical and business aspects of it. This is all my personal opinion, based on the knowledge, information available and limited by my ability to comprehend. I’m not an expert. I’ve also decided to keep a log of the events, as they unroll, in a sort of a Corona diary. And made a Corona virus survival guide – a work in progress. 🙂

1. How the virus spreads, how serious it is

Again, based on the information available and my understanding of it, Corona virus is not much more difficult to overcome by a single person, compared to an average, “ordinary” flu virus. It is a bit more likely to attack the lungs (causing pneumonia), but still not all to bad – in and off itself.

What is the problem with it? The main problem is it spreads much more quickly than “ordinary” flu. Probably because it is a new, mutated sort of virus, so no people have built up immunity for it – and there is still no vaccine (as far as I know).

Another problem is the long incubation period. You can go on for 10 to 12 days without developing any symptoms what soever. For all I know, I might as well have been infected already. Which means anyone I’ve talked with or shook hands with in the last 10 days is already infected. As well as anyone they have contacted in the mean time…

Hence, even though the percentage of people needing hospital treatment for Corona virus is not any greater than the percentage of people needing it for a flu – the number of people needing it in a set period of time is a lot higher. While hospitals have limited capacities.

That is why, in case there is no isolation and the virus spreads, doctors are very likely to get in a position of having to choose who lives and who dies – when there’s fewer hospital beds and respirators than the number of people needing them at a given time.

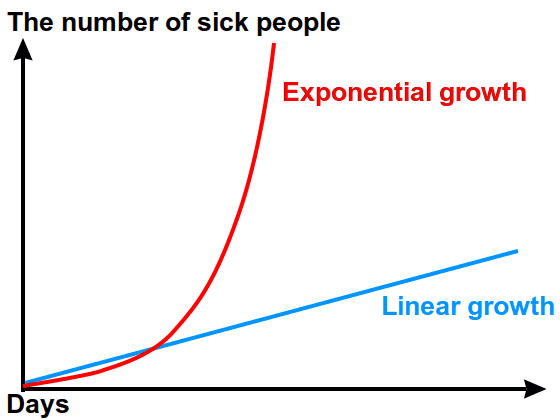

Important thing to grasp is that the virus spreads exponentially. While, because there are no vaccines, the body needs to fight it on its own. In case of hospitalization, a patient is kept on life support, for about 3 weeks, until the body fights it off. That’s 21 days approximately. So, again, if no isolation is implemented, it looks a bit like this:

- Day 1: 1 person sick.

- Day 2: 2 people sick.

- Day 3: 4 people sick.

- Day 4: 8 people.

- Day 5: 16

- Day 6: 32

- Day 7: 64

- Day 8: 128

- Day 9: 256

- Day 10: 512

- Day 11: 1,024

- Day 12: 2,048

- Day 13: 4,096

- Day 15: 8,192

- Day 16: IT’S OVER NINE THOUSAAAND!

- Day 17: 32,768

- Day 18: 65,536

- Day 19: 131,072

- Day 20: 262,144

- Day 21: 524,288

Pictures speak louder than words:

Picture 1

The best (only) way to make the spread of Corona virus follow a linear growth, or even stopping the growth, so that hospital capacity is big enough for all the people needing a treatment, is to isolate people – have as little interaction as possible, so the virus’ spread is limited.

Many governments had failed to grasp this in time: because of the exponential growth, the measures can only be taken too early, or too late. Same goes for many people. Panic doesn’t help, but being reasonable and cautious does.

By the way, the moment for blocking/closing the borders was on the 23rd of January 2020, when China had placed the city of Wuhan under quarantine. Closing the borders at that date and praying that none of the people who have been in contact with anyone infected had already travelled to your country, might have proven to be effective – along with getting soldiers in front of each supermarket, controlling how many toilet paper and disinfectant each person can buy. The moment a country gets even one reported case, because of the long incubation period and very fast spread of the virus, it’s already too late. You already have hundreds infected, that will turn to thousands in a day, or two. So ten, or hundred, or even thousand more people coming in from abroad makes absolutely no real difference.

Another nonsense I see is limiting the number of public transport busses, trains, subways etc. Either ban travel all together, or increase the number of public transport vehicles, so the fewest number of people are stuck together.

2. Ethical choice

I have closed my bicycle repair shop until further ado (still offering on-line consulting for a fee, though 🙂 ). Based on the information I have, the only way for me to sleep well at night is to minimize the risk of infecting anyone, or getting the infection myself – and then infecting anyone.

The obvious downside is, of course, lower income. Which also affects my family and plans. However, I consider human life to be precious and unless risking starvation, closing the shop is the choice I made.

Also, like most people in Europe and the USA, I’m among the lucky ones in terms I don’t work for 1$ per day and do not risk starvation in case I have no income for a month, or two. Many people in the “lucky” countries don’t really, fully, realize how lucky they are – just by having been born in the right place (OK, compared to the EU and the USA, Serbia is probably a lot less nice place to be, but still beats about 80% of the world’s population).

This is my personal choice. Not doing it because I think everyone else should do it and we’d be fine. Of course, I do think that, but have no illusions whatsoever that my choices somehow affect the grand scheme of things. That kind of thinking is bullshit in my opinion. Because I’ve been living and making choices as I have for my entire life, same goes for my parents and grandparents, but that hasn’t prevented my country from doing lots of stupid things (including war atrocities). If a critical mass of people did and thought similarly to me, police and the courts for one would be out of business. 🙂 But they don’t – what I do doesn’t really affect all that many people. It just boils down to making a choice that lets me sleep better at night – nothing more, nothing less.

The small businesses that offer direct customer services will be fucked, sooner, or later. Those who close the shop right away will not even get a “thank you”, while they will be loosing money (and having problems with paying the bills and feeding their families). Yet, it is probably the most responsible thing to do. Governments, of any country (as far as I know, not sure about China) haven’t offered much of a support for this.

3. Panic

Many people these days are panicking. Trying to soothe their panic, many have started stockpiling supplies. Toilet paper, as something large, that can be bought cheaply, offers a sense of being in control – so it is being completely sold out in all the supermarkets, along with flour (at least in my country) and disinfectants.

This results in some people having made year long supplies (many of which will probably go to waste), while others not being able to buy any.

If you have a lot of disinfectant, but the others don’t, you are still a lot more likely to catch the virus. Reasonable, sensible, option would be to buy as little as you need, allowing the others to take the precautions as well. This affects the entire population and needs team work.

(Un)fortunately, human beings are driven by emotions, especially in the times of crisis. It is how it is. Raising the level of consciousness and solidarity is hard. Best way to go in the long run, at least in my opinion, but also the most difficult one. So it is seldom taken – not by governments, corporations, or individuals. Which leads us to the next chapter.

4. Business

During the normal times, for most people, it is perfectly acceptable for say a lawyer to charge for one hour of their lifetime about 10 times more than a bicycle mechanic does. No one complains it being unfair. Some of the arguments are “it takes lots of investment and studying to become a lawyer”. Well, with all the bicycle industry standards changing ever more quickly (to the point that the term “standard” makes no sense, since every manufacturer just throws out new designs, completely incompatible even with their own products from the times before), being a good, competent bicycle mechanic also takes a lot of studying and investment in tools.

But let’s entertain the thought that it’s perfectly fair and reasonable for one person to be valued 10, or 100 times more than another (or 1,000,000 times more in case of some CEOs). This is what most people supporting democracy and capitalism, as a pinnacle of human development, say and believe. That it’s normal for about 1% of the world’s population to hold about 90% of the world’s resources. That it’s normal for an average monkey in the USA to make 10 times more per hour than a similar monkey in Serbia, who, in turn, makes about 10 times more than an average African one…

Now, those same people having firm trust in that scheme of things (“the poor just need to stay positive, work hard…”) are complaining about the others for buying all the supplies. Or, for selling the goods in high demand (like disinfectants) at “unfairly high prices”. “Making money out of other people’s misery”.

Well, once in my life I was falsely accused. Had to pay a lot of money to a good lawyer to prove it (you’d have to take my word for it that I was 100% innocent and doing what was both ethically and legally correct – even though the two are often mismatched, but weren’t in this case). Was the lawyer making money out of my misery?

Another point: how much does an iphone cost – to design, build and distribute? Isn’t that company making billions in profits? Does anyone consider any large corporation to be making money out of other peoples misery/stupidity/emptiness/impulse shopping…?

Now the things are starting to shake up a bit, and an average person is getting a bit closer to what life in poor, undeveloped countries looks like – in terms of safety, life expectancy etc. All of a sudden, everyone is talking about things like “fairness”, “solidarity”, “not making a profit out of other peoples’ misery…”.

For the poor – every month, every day, is an emergency. Yet no one considers this. No one minds the Chinese workers being paid little, and working in inhumane conditions to build the damn iphones. No, if it means they would cost 100$ less than the already outrageously high price, it’s all fine and dandy.

However, if anyone buys a lot of disinfectant in time and sells it at a profit similar to those made by the large corporations on a regular basis – they are the villain! To avoid any misunderstanding (read chapter 2), I think this kind of doing business is short-sighted, inhumane, harmful in the long run – just like most of capitalism. But that’s the way capitalism is supposed to work:

- You buy things when they are cheap, and can reasonably expect the price to go up later.

- You sell at the highest profit possible.

Have you ever heard anyone asking for a pay cut? Just because of the poor people who can’t afford their product? Does anyone even stop to consider how much our consumer society damages the whole ecosystem, the whole Earth? Buying new computers, phones and cars every few years. Urging people to do it. Business as usual.

Now, someone is making a profit out of “normal, average people” we are surrounded by, including ourselves. And many are outraged about how evil it is. It’s normal capitalism: some people were “smart” enough to predict the high demand, so they “invested” in larger stocks of some products, and are now selling them for a profit.

5. The solution

Just like with loosing weight (another problem of modern folk in developed countries) – the solution is clear: eat healthy food and exercise. Yet, for many it is impossible task. Many people who are “on a diet” use elevators to get to the gym – to which they came by a car, not walking or cycling. 🙂

Likewise – solution to this global crisis, as well as to the oncoming global warming, overpopulation and lack of food and clean water for many people, is really simple, yet the most difficult to enforce: solidarity.

Tossing capitalism and consumerism to the thrash. With communism being the ultimate goal: no money, no borders, everyone contributing as much as they are able/willing and everyone sharing as much as we all have. No more, no less.

I grew up in a communist run socialist Yugoslavia. And it was a nice country to live in. Full employment, free education and medical care, and rapidly developing infrastructure and industry. At least for my country, Serbia, never before and never after has an average man lived better. It was a humane society with a lot of freedom. In modern capitalist democracy, you must obey the corporate bosses, or starve. You are free to starve.

A complaint I often hear is that people don’t work very hard when they don’t have to. Well, my father for one was a very hard working man, even in the “communist times”. I am a very hard working man. With high enough level of consciousness and solidarity, most people would feel ashamed and worthless for not contributing. Being competent and hard working to invent new things, improve the current state of affairs, the respect gained by the colleagues and clients for doing a good job are all rewards in and off themselves.

With education, housing and medical treatment being equally distributed, there is no incentive to hoard a lot of resources for one’s self. In such a society, that is something to be frowned and looked down upon. Unlike capitalism, where having 1,000 lifetimes of other people’s work at one’s disposal is the ultimate goal.

So the way out of all this nonsense, the goal worth striving for, is communism. Capitalism supports and encourages accumulation of resources, selling as much as possible for as much as possible, creating an advantageous market position to make even more profit (ring a bell now?)…

Say I have a few tons of toilet paper and hectoliters of hand disinfectant. Should I sell it at a high price, so only those who really need it will buy it, with the risk of the poor not being able to buy it no matter how much they need it? Or give it away, risking other hoarders of taking more than they need? In my opinion, the only sensible option is rationing: done by a well organized government.

I’ll end this with a series of quotes by one of the worlds richest men, Warren Buffett (many of those are in fact criticizing the modern capitalism):

Take the job that you would take if you were independently wealthy.

I’ll tell you why I like the cigarette business. … It costs a penny to make. Sell it for a dollar. It’s addictive. And there’s fantastic brand loyalty.

Someone’s sitting in the shade today because someone planted a tree a long time ago.

I don’t have a problem with guilt about money. The way I see it is that my money represents an enormous number of claim checks on society. It is like I have these little pieces of paper that I can turn into consumption. If I wanted to, I could hire 10,000 people to do nothing but paint my picture every day for the rest of my life. And the GNP would go up. But the utility of the product would be zilch, and I would be keeping those 10,000 people from doing AIDS research, or teaching, or nursing. I don’t do that though. I don’t use very many of those claim checks. There’s nothing material I want very much. And I’m going to give virtually all of those claim checks to charity when my wife and I die.

It’s class warfare. My class is winning, but they shouldn’t be.

The free market’s the best mechanism ever devised to put resources to their most efficient and productive use. … The government isn’t particularly good at that. But the market isn’t so good at making sure that the wealth that’s produced is being distributed fairly or wisely. Some of that wealth has to be plowed back into education, so that the next generation has a fair chance, and to maintain our infrastructure, and provide some sort of safety net for those who lose out in a market economy. And it just makes sense that those of us who’ve benefited most from the market should pay a bigger share. … When you get rid of the estate tax, you’re basically handing over command of the country’s resources to people who didn’t earn it. It’s like choosing the 2020 Olympic team by picking the children of all the winners at the 2000 Games.

I happen to have a talent for allocating capital. But my ability to use that talent is completely dependent on the society I was born into. If I’d been born into a tribe of hunters, this talent of mine would be pretty worthless. I can’t run very fast. I’m not particularly strong. I’d probably end up as some wild animal’s dinner.

But I was lucky enough to be born in a time and place where society values my talent, and gave me a good education to develop that talent, and set up the laws and the financial system to let me do what I love doing — and make a lot of money doing it. The least I can do is help pay for all that.

The 400 of us pay a lower part of our income in taxes than our receptionists do, or our cleaning ladies, for that matter. If you’re in the luckiest 1 percent of humanity, you owe it to the rest of humanity to think about the other 99 percent.

You want to be greedy when others are fearful. You want to be fearful when others are greedy. It’s that simple. … They’re pretty fearful. In fact, in my adult lifetime, I don’t think I’ve ever seen people as fearful economically as they are right now.

Some material things make my life more enjoyable; many, however, would not. I like having an expensive private plane, but owning a half-dozen homes would be a burden. Too often, a vast collection of possessions ends up possessing its owner. The asset I most value, aside from health, is interesting, diverse, and long-standing friends.

My wealth has come from a combination of living in America, some lucky genes, and compound interest. Both my children and I won what I call the ovarian lottery. (For starters, the odds against my 1930 birth taking place in the U.S. were at least 30 to 1. My being male and white also removed huge obstacles that a majority of Americans then faced.) My luck was accentuated by my living in a market system that sometimes produces distorted results, though overall it serves our country well. I’ve worked in an economy that rewards someone who saves the lives of others on a battlefield with a medal, rewards a great teacher with thank-you notes from parents, but rewards those who can detect the mispricing of securities with sums reaching into the billions. In short, fate’s distribution of long straws is wildly capricious.

The reaction of my family and me to our extraordinary good fortune is not guilt, but rather gratitude. Were we to use more than 1% of my claim checks on ourselves, neither our happiness nor our well-being would be enhanced. In contrast, that remaining 99% can have a huge effect on the health and welfare of others. That reality sets an obvious course for me and my family: Keep all we can conceivably need and distribute the rest to society, for its needs. My pledge starts us down that course.

The most common cause of low prices is pessimism — some times pervasive, some times specific to a company or industry. We want to do business in such an environment, not because we like pessimism but because we like the prices it produces. It’s optimism that is the enemy of the rational buyer.

I’ve reluctantly discarded the notion of my continuing to manage the portfolio after my death — abandoning my hope to give new meaning to the term “thinking outside the box.”